|

|

Brief History of the Institution Brief History of the Institution

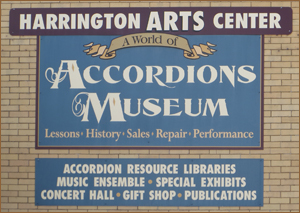

Founded in 1993, the Museum is dedicated to educating the public about the importance of accordion-family instruments' contributions to cultures of the world by displaying and preserving historic instruments, music, recordings, documents, and artifacts. World-class artists are sponsored in public concerts, and scholars are encouraged to research related disciplines.

A World of Accordions Museum (AWAM) docents present history as interesting and relevant to modern life, sometimes through stories that personalize the role of accordions in individual families. AWAM accepts donations, provides IRS deductible receipts, and recognizes donors in attribution plaques.

The Museum began as a subsidiary of Accordion-concertina Repair and Technicians’ School (Duluth, MN, 1994), from which the acronym ARTS is retained in Harrington ARTS Center (Superior, WI, 2000).

The repair school curriculum was devised by Helmi Strahl Harrington, Ph.D., and taught in her department at Red Wing Technical College (Red Wing, MN, 1991-1993). When the Minnesota legislature merged higher-education system finances and greatly compressed technical colleges’ resources, her department was eliminated along with many others. Having received substantial publicity resulting in long lists of potential students, she started ARTS as a specialized school of higher education. Students from throughout the USA and several foreign countries studied Harrington’s 450 instruments designated as museum examples, while practicing skills on a smaller number of donated and purchased pieces. At this point, the repair school was more prominent than the museum in the public eye. In 1998 the newly named A World of Accordions Museum (AWAM) became a separate entity. Upon recommendation by Faithe Deffner in 1999, the American Accordionists’ Association, International affiliated with AWAM during the presidency of Dr. Carmelo Pino. This was also the year in which the museum received its first musical estate of a world-prominent musician—Charles Magnante.

Incapable of housing both the school and 1,000 museum instruments, displays were moved to Superior, WI, reopening in 2002 as part of Harrington ARTS Center. Repair seminars share space at the new facilities as well as at the original site, (2801 West First St., Duluth), and continue to attract national and international participants. Incapable of housing both the school and 1,000 museum instruments, displays were moved to Superior, WI, reopening in 2002 as part of Harrington ARTS Center. Repair seminars share space at the new facilities as well as at the original site, (2801 West First St., Duluth), and continue to attract national and international participants.

The museum annually attracts about 2,000 visitors including tourists exploring our national attraction, music aficionados, researchers and scholars. Our displayed instruments now number 1,300, are a feast for the eyes and a revelation in cultural and ethnic histories. When sounded in demo-concerts, their various aesthetic underlays amaze all.

HARTS and its subsidiaries is operated as a non-profit organization overseen by an illustrious slate of directors.

First Accordion of the Harrington Collection

In 1966-67, I was in the Music Department Graduate School at the University of Houston. We students were all serious and hardworking - not a slouch in the bunch! many of my classmates went on to receive Ph.D.s or DMAs, some took academic positions, a couple  continued performing, one is a recognized composer and now chairs that very same music department. continued performing, one is a recognized composer and now chairs that very same music department.

The fellow student I most respected, Ivar Mikashof, went on to teach applied piano at SUNY (New York). Some years after graduation I saw a photo of him in a national magazine like Time or Life, in which the caption mentioned his success as a teacher, and the awards his students were winning. But then, we shared classes, an occasional cause, and a piano teacher, Prof. Albert Hirsh, head of the Applied Piano Department.

I was dreaming of concert pianist status, maybe writing a few brilliant articles - shooting toward the elite of the academic world! Ivar introduced me to MENSA - a path we shared for only a short while.

The academic world I was experiencing seemed very detached from the one in which I earned a living outside school - playing and teaching accordion. the lesson that underlay my reluctance to talk about my work came from the mouth of a college instructor several years earlier: "What is a person like you doing playing an instrument like that?"

But Ivar was among the few who knew I was an accordionist. He mentioned he had a very old button accordion he'd like to give me. Perhaps I could do something with it, he certainly couldn't, he said. On the afternoon I was to pick up the instrument, I waited next to Ivar's grand piano. there he was, a great talent with his great piano. And there was I, feeling insignificant, holding the least member of the accordion family. I was such a snob, both in musical repertory and in the instruments on which to perform. My blossoming ego felt a pang to be association with this mere "toy," while the grandeur of the piano and its monumental owner stood nearby. All my visions were suddenly in turmoil. While I was amazed at the gift itself and while I admired this little item, the thought first crossed my mind that not every accordion can or should be valued only for its playability. Some deserve to carry out retirement in a museum where people admire facades and honor the history they represent. But the USA had no such museum. "I wonder if I..." came to unexpected thought. That quiet moment even then had a sense of prescience. But Ivar was among the few who knew I was an accordionist. He mentioned he had a very old button accordion he'd like to give me. Perhaps I could do something with it, he certainly couldn't, he said. On the afternoon I was to pick up the instrument, I waited next to Ivar's grand piano. there he was, a great talent with his great piano. And there was I, feeling insignificant, holding the least member of the accordion family. I was such a snob, both in musical repertory and in the instruments on which to perform. My blossoming ego felt a pang to be association with this mere "toy," while the grandeur of the piano and its monumental owner stood nearby. All my visions were suddenly in turmoil. While I was amazed at the gift itself and while I admired this little item, the thought first crossed my mind that not every accordion can or should be valued only for its playability. Some deserve to carry out retirement in a museum where people admire facades and honor the history they represent. But the USA had no such museum. "I wonder if I..." came to unexpected thought. That quiet moment even then had a sense of prescience.

Over the course of decades, I kept track of Ivar's accordion among my possessions. Despite the pleasant memory, it was not one of my favorite instruments - I still saw it as common, undistinguished, small, inadequate - and fragile. Even when it was new, it had limited vocabulary, and now, no remaining musical value. Under other circumstances, I would not have given it a second glance.

Many years, many tears, and a major shift in focus had to occur before my museum became a reality, and even a few more before the little accordion found a rightful place of honor on the shelves. In selecting for primary focal points, it was regularly overlooked in favor of the more beautiful, unique, exalted and demanding instruments. Each one that found the spotlight has a reason to be there, but only now, as the museum approaches monumental proportions, have I accepted the importance of this 'First."

Actually, its very ordinariness is the connecting thread, the core of the museum collection itself. It is the modest, the everyday, salt-of-the-earth people who invented the accordion, reinvented and made it popular. And for a person at the turn of the 20th Century, this very instrument might well have been the finest piece of artistry in the home. Ordinary people formulate and establish culture and the music that perseveres. Masses loved the simplicity of the one-row button diatonic accordion, and countless varieties were produced throughout the world. The little box could preserve memories of old ways and old times; younger craftsmen looked optimistically toward the future and amended tradition. this common instrument is a root for endlessly aggrandized models in the history of accordion construction. All of these should be documented and exhibited with pride in the museum.

For its time, the 13" by 6.5" instrument was probably quite pretty. The first owner's eyes undoubtedly delighted in the gold pallets, brass ornaments, lively and colorful papers. An expert told me some fourteen colors, in as many required steps, were used to produce the paper, and that it is an exquisite example of late 19th Century border work. Another one-row button diatonic accordion in the museum uses this border paper, a "Kosmos" made by Gessner in Magdeburg, Germany. Although the instruments are substantially different, they probably originate from the same decade. Walnut burl seems to be the wood veneer used for the exterior treble and bass pans. Two keys (crossed) in scalloped triangles are found on the instrument, the most noticeable being connected by the words "Fabrik Marke" on the treble pan. Another paper is glued and tacked to the top. it reads: "Lames d'Acier Incassables." A brass plaque behind the treble keyboard reads in French: "Clavier/Perfectionne Demontable/Registre Sous No. 4078."

Attached to the pan is a single row of buttons and pallets, and on the underside, two diatonic rows of reeds in a scale that was probably "A".

At present, the instrument remains unrestored: some reeds are missing, most are in poor condition; a section of treble-pan framing must be replaced; the bellows need help, among other cosmetic details. nonetheless, this instrument becomes more precious to me with each expansion of the Museum and with every piece of publicity that brings larger-scale recognition. Some day soon, the respect and true personal status this instrument deserves will be realized through restoration work that says "Thank You" most appropriately.

Throughout the years, I have thought fondly of Ivar, wanted to find him again and tell him what his gift inspired. Only recently I was told he had died a few years ago. I deeply regret that his brilliantly gifted life was cut short, and I'm so sorry that I cannot tell my friend his perhaps minimally considered decision had consequences of unexpected proportion.

Now adays, more than 1300 instruments are displayed at the Museum facility in Superior, WI with further instruments awaiting repair and/or rotation into the display or traveling display. Instrument No. 1 sit proudly among its fellow members of the accordion family as part of the magnificent World of Accordions Museum display.

Helmi Harrington, Ph. D |

|